Why Do Men Dream of Rome?

Our times revive a curiosity about the only Empire in History to rival America.

Dateline: December 21, in the Year of Our Lord 2023

This is a preview of an article I wrote for The Classical Difference, to be released in January 2024.

New York has been called the city that never sleeps, the big apple, and the world’s melting pot. It has been the cultural bellwether of America since the 19th century. Sadly, there seems to be one culture that’s disappearing: America’s. After recently visiting Nairobi, Kenya, I’m not certain if Nairobi’s vibe or New York City’s is further from middle America. The closest remnant of American culture in New York, post-COVID, seems to be the decadent echo of American consumerism still on display in Times Square. Glitz, glare, shops, entertainment, and sensory overload is displayed alongside homeless people, drug addicts, and the naked (except for body paint) exhibitionists. The city somehow has become a place of show-trials, election corruption, and erosive media.

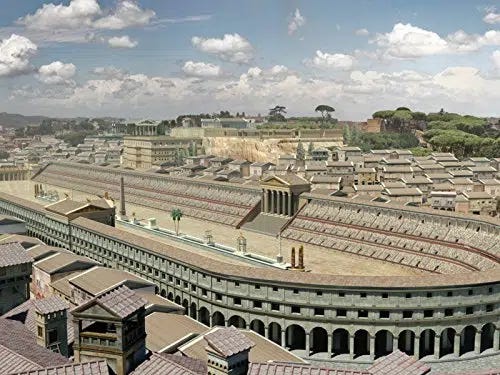

Ancient Rome had its own sort of Times Square. I wonder what that last chariot race in Rome’s Circus Maximus was like in 594 AD? By that time, chariot racing in the Circus had long drifted from its lofty position as a show of Roman leisure and greatness. Did it resemble Times Square as we now see it?

Sometime near 700 BC, the early kings of Rome used the valley between the Palatine and Aventine hills to race chariots. As the great Roman Republic grew and became powerful, so did the Circus. In the Republic’s waning years, Julius Caesar built the grand and glorious Circus Maximus, where men came from far and wide for a chance at glory. Many more came from around the world to watch. This seems to be an historic trend: When a civilization reaches ideological decline, its wealth holds on for a while and it builds great cultural showpieces in a seeming attempt to hold on to greatness. Contemporary sources claimed that 250,000 spectators cheered on the bravery and skill of those who raced in the Circus Maximus. For reference, Bristol Motor Speedway is the largest known venue in the U.S. with seating for 146,000 (ironically, also a racing venue). Other tracks might be larger, but none that I could find are estimated to fit as large an audience as the Circus Maximus.

As the Republic’s ideals gave way to the high Empire of Rome, the Circus became more sensational. A thousand-year-old obelisk was brought from Egypt and erected in the median of the Circus, furthering worship of the sun god. Incidentally, New York imported its two-thousand-year-old Egyptian obelisk and placed it just north of Times Square, in Central Park. In Nero’s insane decadence, the wooden structures around the Circus burned and were eventually replaced with stone by the Emperor Trajan c. 100 AD. Through the high Empire, idolatry in the Circus increased. Several temples to deities like Ceres, Luna, and Venus were erected nearby. Bread was famously thrown to appease the crowds, and sensational showmanship became part of the entertainment—including gladiators. The last race in 594 AD was overseen not by a Roman, but by an Ostrogoth king named Totila. The name “circus” came to be applied to shows of great spectacle in the 1700s, and eventually “circus” became a word that we use for organized craziness (i.e., Times Square is a circus!).

Instead of a circle (circus), America has its square. Each time I go to Times Square, it seems to have more jumbotrons. It’s as though we’re replacing the light of greatness with photon generating illusions. But, there is hope. In the same decade that the Circus Maximus fell silent, the Irish monk Columbanus was founding monasteries in Ireland that would become repositories of learning, preserving books and Christian thought. In the same century, Cassiodorus was founding classical Christian Schools in Britain. And Boethius, who was born in Rome, fled the decadence to Pavia in what is now northern Italy. His work in the church and academia is still read today. He reconciled Aristotle and Plato with Christian theology and is a father of classical Christian education.

His life echoes strangely in our time. Boethius was a well-reputed political leader until he started to root out corruption in the government bureaucracy. He and his sons were soon falsely accused of treason and, although the basic facts were not in dispute, their interpretation was highly unusual. What was claimed to be technically fraudulent was open and common practice, though others were not prosecuted. Nonetheless, a threatened political bureaucracy sentenced him to death (although exile was the normal penalty for his alleged crime), and he was bludgeoned to death. He is regarded as a Christian martyr.

The outer territories of the old Roman empire in the 6th and 7th centuries would become the next center of Christian greatness through classical Christian education and the church. In this light, our times are an opportunity. As our cities decay, we can participate in the dawn of a return to the order of Christianity which will, one way or another, replace decadence with hope, civilization, and light. Rome’s path is well worn. America, it seems, still lives in the shadow of the “eternal city.”

David Goodwin